Pakistani Cinema: Then, Now and Later

Ali Ahmad

Lahore: From its golden age in the 1950s and early 80s, to its tragic downfall and later to its ‘revival’ in the 2000s, Pakistani cinema has been on a rollercoaster ride.

On one side it was neglected by authorities, petty politics, plagued by piracy and draconian censorship, among many other issues. On the other side, its texture of creativity, innovation and commercial success gave some masterpieces to the country. Sadly, while the country’s cinema saw brilliance over the years, it was also tainted with complex issues and extreme challenges that reduced it to ashes.

In the early 50s to late 60s, Pakistan’s film industry was thriving. It was showcasing originality, depth, craft, and character both in terms of content and audience. Iconic filmmakers made brilliant films. Directors like Pervez Malik, S Suleman, Hasan Tariq, and Shabab Kiranviand Nazrul Islam were instrumental in creating memorable films and shaping cinema.

Hits like “Dou Ansoo” (1950) that kept the viewers hooked to the screen with its plot, and “Neela Parbat” (1959) with its dynamic storytelling set the stage for an industry that later produced many other hits with gripping storylines and modern production.

Pakistani cinema also boasted of its musical excellence – and talented music directors such as Sohail Rana, Naushad, and Khwaja Khurshid Anwar, composed memorable soundtracks.

There were actors who became the face of the Pakistani cinema – Waheed Murad, Muhammad Ali, Shabnam, and Zeba gained immense popularity and became cultural icons.

There were other things that were going well for the industry: prolific production of films, diversity in storytelling and cultural reflection to an extent.

But the industry faced a sharp turn in the late 1970s, after the military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq came to power. This time was marked by political turbulence, economic downturns, societal change, and a tightening grip of censorship which cast its long shadow over all kinds of artistic expression.

With the Islamization period under General Zia, censorship in the ‘80s worsened. Budgets shrunk, equipment became outdated, and the overall quality dropped low. Pakistani cinemas faced tough competition from Hollywood and Bollywood filmsleading to a decline in the audience. The industry had low production values, outdated technology, and a lack of innovation. The overall quality suffered immensely. Meanwhile, even though the middle conservative right did not raise direct objections to films, they did begin to intervene in movie narratives. A wave of moralistic films were released where Islamic values became predominant.

Meanwhile, even though the middle conservative right did not raise direct objections to films, they did begin to intervene in movie narratives. A wave of moralistic films were released where Islamic values became predominant.

Still gems like “Zinda Laash” (1967) and “Aaina” (1977) made their way and left their mark. A notable mention is “Maula Jatt” (1979), which although was a low budget film, was a trendsetter and is now considered a classic. This was also the first film to be banned because of its violence and gore, but was later reinstated after their removal.  Maula Jatt’s plotline caught on and by the 1990s, this became formulaic. Unfortunately characters became repetitive and stories monotonous. Audience became more niche – mostly from working classes – who went for pure entertainment even exploitation rather than intellectual stimulation. Now the audience too was not as diverse and movies became base entertainment.

Maula Jatt’s plotline caught on and by the 1990s, this became formulaic. Unfortunately characters became repetitive and stories monotonous. Audience became more niche – mostly from working classes – who went for pure entertainment even exploitation rather than intellectual stimulation. Now the audience too was not as diverse and movies became base entertainment.

With satellite and cable television in the 90s, many people opted to stay indoors rather than go to the movies. They began to lean towards tele-dramas. Video discs were the new trend in market, luring the audience away from cinema halls. If in the ‘70sthere were 1000 cinema houses across the country, by the end of the ‘90s, this number had fallen to a third.

As the moral lessons in the films grew, so did the power and influence of conservative sections of society. And with losses upon losses, more cinemas began shutting down.

One of Lahore’s iconic cinemas in the old city -Pakistan Talkies was locked up. In the past decade or two, it has even screened objectionable movies, as could be seen through its shutters where vulgar posters were on display. At the turn of the millennium, a couple of projects led by maestro Shoaib Mansoor marked a flickering resurgence of cinema and a growing sense of excitement among the public of visiting the cinema once again.

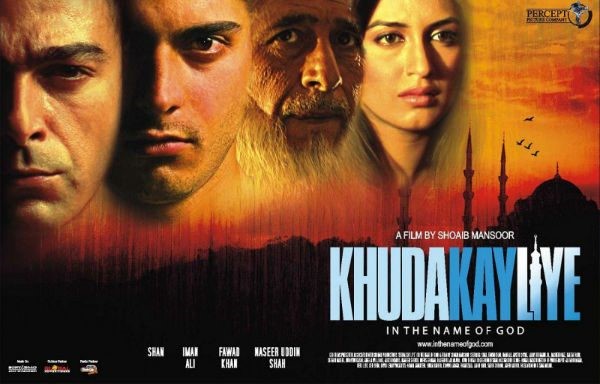

At the turn of the millennium, a couple of projects led by maestro Shoaib Mansoor marked a flickering resurgence of cinema and a growing sense of excitement among the public of visiting the cinema once again.

This time, tastes had changed drastically and people were more accepting of a more liberal culture. There was censorship but within limits.

There was more experimentation and fresher narratives and storylines.

“Khuda Kay Liye” (2007) was the first of this wave and in a long time, the audience saw something heartfelt and politically impactful what with the ongoing US War on Terror.

Mansoor’s own film “Bol” (2011) continued the progression while Afia Nathanial’s “Dukhtar” (2014) on an important social issue revisited the core of storytelling – something closely associated with Pakistan’s dramas in the past. And yet the path to revival wasn’t all roses. The industry continued to grapple with piracy, lack of screens, and the need for financial investment. The pressure of conservative forces along with continuous censorship made it difficult for filmmakers to even think of something out of the box.

And yet the path to revival wasn’t all roses. The industry continued to grapple with piracy, lack of screens, and the need for financial investment. The pressure of conservative forces along with continuous censorship made it difficult for filmmakers to even think of something out of the box.

Films like “Javed Iqbal” and “Zindagi Tamasha”, received critical acclamation at international level but never even saw the light of the day (or the cinema projector) in their own country. Even the highest grossing Pakistani film of all time, “The Legend of Maula Jatt” (2022) was delayed almost 2 years because of censor board intervention and saw the screens after several changes were made to the original.

Struggling, the Pakistani cinema still attempts to stand on its feet, with independent films like “Cake” (2018) and “Laal Kabootar” (2019), and more recently ‘In Flames’ and ‘Kamli’ which have been played in prestigious film festivals, and the latter two nominated in the 96th Academy Awards and Minsk International Film festival respectively, showcasing the industry’s potential on a global stage.

The prowess of actors like Fawad Khan and Sajal Aly transcended borders, proving that Pakistani talent can stand shoulder to shoulder with the best.  As the reel continues to spin, the future promises some potential – on the condition that the creativity is allowed to shine. The rise of digital platforms and streaming services presents an opportunity for storytellers to captivate global audiences without the constraints of traditional distribution channels. Collaboration with international filmmakers and integration of modern technology can also help the industry a lot.

As the reel continues to spin, the future promises some potential – on the condition that the creativity is allowed to shine. The rise of digital platforms and streaming services presents an opportunity for storytellers to captivate global audiences without the constraints of traditional distribution channels. Collaboration with international filmmakers and integration of modern technology can also help the industry a lot.

Moreover, if the government decides to tone down the censorship and focus on investing financially in the industry, the potential and reach knows no bounds.

Ali Ahmad, a student of the FC College in Lahore, juggles his studies with a creative position at an advertising agency.

Comments are closed.